What is a phase of matter?

And why do you keep hearing that we’ve discovered a new one?

If you follow scientific announcements, there is a flavor of article that you’ve probably seen a few times: “Physicists discover/create a new phase/state of matter”. Most recently, Microsoft made such an announcement related to their quantum computing work:

The topoconductor, or topological superconductor, is a special category of material that can create an entirely new state of matter – not a solid, liquid or gas but a topological state.

However, this is only the most recent example in a long line of press releases from any number of researchers over the years.

These announcements often capture the imagination of the public1. They sound very exciting: like maybe we need to revise our ancient elementary school textbooks to include a new addition to solids, liquids, and gases.

But what do they really mean?

Elementary school phases of matter, revisited

If your elementary (or primary) school education was like mine, at some point you learned that the basic phases of matter2 were solids, liquids, and gases. Furthermore, you learned some criteria to distinguish these: solids are rigid and hold their shapes, liquids can move freely but do not expand to fill a container, and gases fill a container. You might have also learned that substances like water can change between these phases, in phase transitions at certain temperatures. If you are like me, you found all of this reasonable and in agreement with your perceptions of the world.

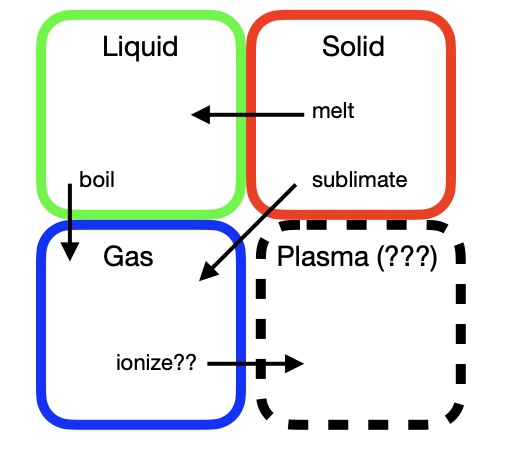

However, if your education was like mine you also were eventually told that there was a fourth phase of matter, called plasma, that is rare on Earth but makes up stars. I remember being pretty confused and a bit annoyed about this, because these explanations didn’t actually say much about how to tell a plasma from another state, such as a gas. In particular, they didn’t give a nice clear test in terms of the ability to deform to or expand into a container.

An approximate rendering of the “elementary school” concept of phases of matter. There are three clearly defined categories, solids, liquids, and gases, with possible transitions between them. There is also one outlier that doesn’t seem to quite fit in, plasmas.

These questions about plasmas were the first sign of a deeper problem. Over the years, physicists have developed a meaning for “state of matter” that is different from the everyday meaning. These two meanings are constantly getting muddled up in descriptions of scientific discoveries, in a way that leads to much confusion and misunderstanding.

Phases of matter for a physicist

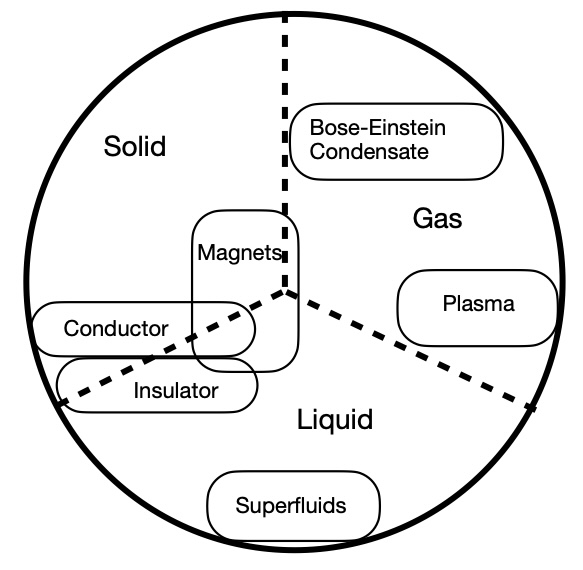

The modern scientific study of phases, and especially phase transitions, dates back to roughly the 1930s. Starting from around that time, abrupt changes in physical properties such as the melting of ice into water were given a precise definition and started to be classified and examined. Once this definition3 was established, it became clear that it applied to changes beyond those from solid -> liquid -> gas. For example, a magnetic material, such as you might have stuck to your kitchen refrigerator, can eventually become demagnetized as it is heated. This demagnetization shares key traits with the phase changes of water, even though the magnet itself remains a solid during the whole process. Therefore, physicists came to consider any material that has the correct sort of abrupt change in its properties as a “state of matter.” This is a huge broadening from the elementary school version in two ways:

- There are now countless possibilities for states of matter, basically as many as there are types of substances.

- States are matter are now non-exclusive. Magnetism can define a state of matter, as can electric conduction or insulation. Each of these can coexist with each other and with the solid/liquid/gas classification. Therefore, a particular substance can be a realization of several types of states of matter at the same time.

An extremely crude and imprecise rendering of the physicist conception of a state of matter. There are many overlapping states with different definitions, of which solid, liquid, and gas are merely three significant examples (which may or may not be distinct phases in different contexts, hence the dashed lines). Some are relatively familiar, such as magnetic materials, while some like Bose-Einstein condensates are very exotic. There are still transitions, too, but I couldn’t even begin to add those in.

A failure to communicate (clearly)

There are a number of examples in physics in which something with an everyday name is co-opted to have a precise scientific definition. For example, if you exert yourself pushing against an immobile wall, you may feel that you have done some “work,” but according to the physicists’ definition of work you actually have not. When communicating results to the public, these double meanings should be watched with extreme care.

So it is with states of matter. When a physicist says that they have created/observed/discovered a new state of matter, in everyday language what they really mean is much closer to saying that they have found a new type of material. It is interesting, and potentially useful, but it is not automatically a revolution, nor is it comparable to finding an alternative to solids, liquids, and gases. Returning to the Microsoft announcement, the state that they are claiming to have created is a particular behavior of the electrons within a chunk of material (a semiconductor/superconductor mixture), so it is misleading to imply that it is not a solid. It is a solid, but one with potentially interesting electronic properties.

My point here isn’t to shame anyone. Indeed, even popular descriptions of the research I have myself contributed to have veered into this language. But I do think that scientists can do a better job of clearly explaining what our work is and isn’t adding to the body of knowledge. And perhaps, if we can give the public a more accurate picture of the possible meanings for “state of matter,” future schoolchildren won’t have to be as confused as I was.

Some further reading (more technical):

More is the Same: Phase Transitions and Mean Field Theories, by L. Kadanoff. A nice perspective on the history and significance of phase transitions (free pdf).

Lectures on phase transitions and the renormalization group, by N. Goldenfeld. A standard reference to the subject (paywalled book).

See, for example, this very excited news coverage of how “the laws of matter may have changed” ↩︎

I have occasionally seen people try to distinguish between “phases” and “states” of matter, but I don’t think that any distinction is consistently used or recognized in the public eye. In this post, I use both as complete synonyms. ↩︎

I can’t totally specify this rigorous definition of a phase without an extended series of equations, but here is my best attempt: a range of values for some control parameter, over which the free energy density of an infinite sample of some substance is everywhere described by an analytic function. Modern physics has actually moved beyond even this definition, to include phases that are not defined by the free energy, but this does not affect the point being made here and we must walk before we can run. ↩︎