What makes quantum physics special?

A brief tour through eighty years of answers (photo credit: one of the most popular images used to abstractly convey quantum physics. original author unknown)

Quantum physics is, at least by reputation, famously strange, counter-intuitive, and hard to understand. A quick internet search will turn up an endless scroll of quotes by eminent physicists saying this, so it must be true.

However, it is easier to talk about its mysteriousness, writ large, than to pinpoint the exact qualities that make it so. In this short post I will look at attempts to answer the question: What are the essential attributes that distinguish quantum behavior from “everyday” classical behavior? In a sense this is probably a hopeless question, like trying to identify the most important note in a symphony. However, the evolving answers make an interesting window into, if not the nature of the theory itself, at least our understanding of it and the aspects that interest us most. While it starts at ideas that are familiar to most people with a casual interest in physics, the most recent developments are largely unknown outside of experts in the relevant subfield.

What follows is a schematic and loosely historical guide to how people have answered this question. I should make it clear that I’m approaching this question as an interested amateur, not an expert, and entirely describing the contributions of others. Any errors in such descriptions are, as always, my own.

1. Superposition (c. 1935)

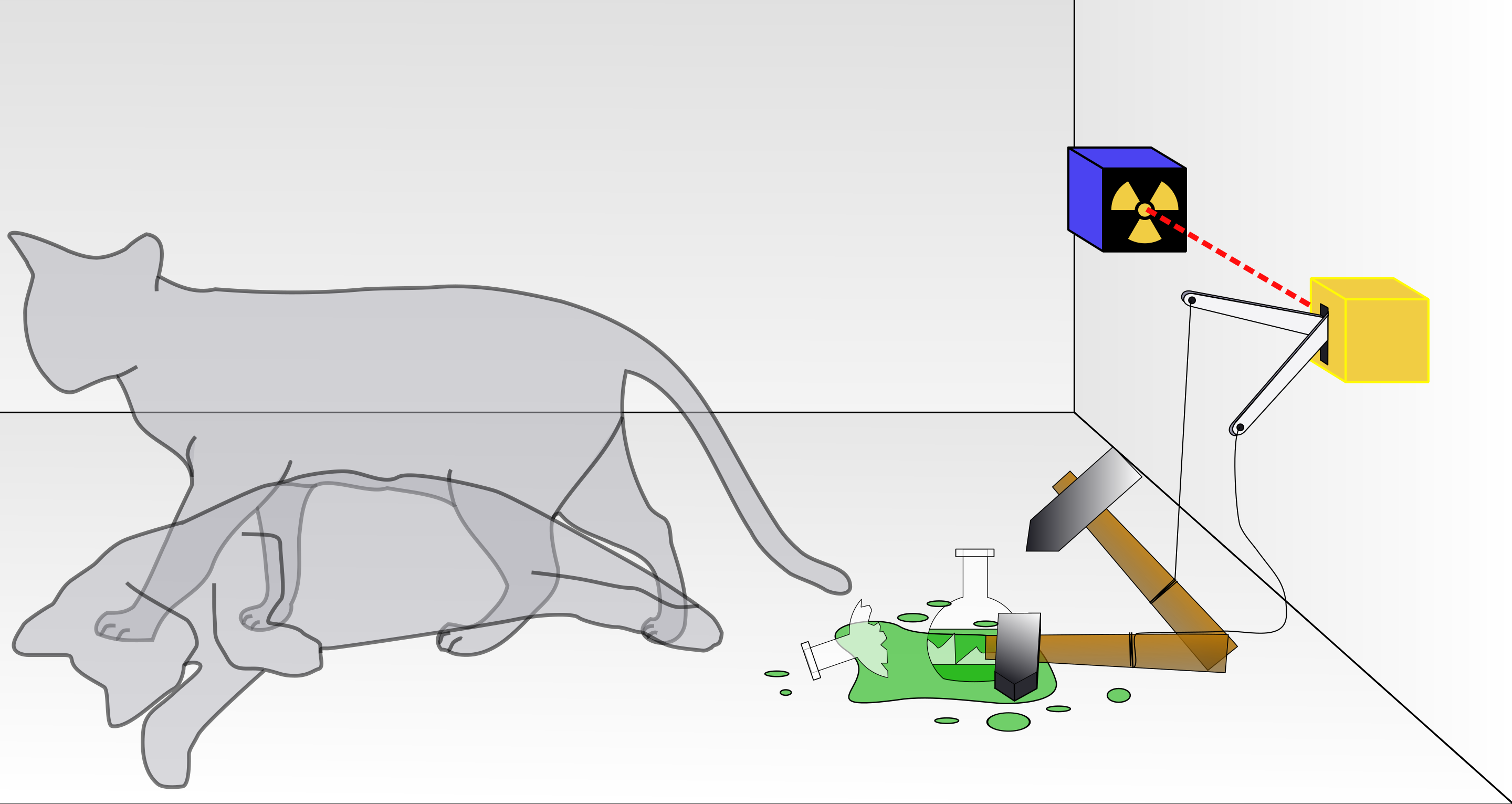

Wiki’s rendering of the Schrödinger’s cat thought experiment. Credit: wiki user Dhatfield.

Early quantum physics founders, such as Schrödinger, found it understandably strange that its laws allow any system which has two possible states to also be in a “superposition” of these two states, in which the probability of observing either state is distributed into a mathematical wave that can interfere with itself. The Schrödinger’s Cat thought experiment was an attempt to show how absurd this feature seemed when brought to our everyday life.

That said, while superposition of cats is odd enough, in other contexts superposition does not surprise us. Superposition of light beams is familiar in everyday life and was precisely understood by physicists for decades before quantum theory.

Another problem with locating superposition as the key to quantum strangeness is that superposition is basis-dependent, which essentially means that it is a subjective judgement rather than an absolute one. For a polarized spin-half particle, whether it is in a superposition or not depends wholly on the direction from which one looks at it 1. So as a demarcation line, superposition alone doesn’t work so well.

2. Entanglement (also c. 1935)

The classic attempt to visualize entanglement: a mystical glowing link between two particles. Hey, it’s as good as anything (stock photo).

Entanglement is the condition in which two quantum objects are in a joint superposition. The measurement of either one individually is not deterministic, but the result for one seemingly determines the result for the other, even though they may be on opposite sides of the Universe. A famous 1935 paper by Einstein and collaborators 2 argued that this feature must mean that quantum theory is incomplete, and subsequent work by Bell 3 made explicit the ways in which certain entangled systems can violate reasonable-seeming assumptions about the underlying nature of reality.

This is probably still the answer that you will hear most often from physicists—after all, who would want to contradict Einstein? However, the 21st century has brought some nuance to this answer as we look at quantum physics through the lens of computation.

3. Magic! (c. 2000)

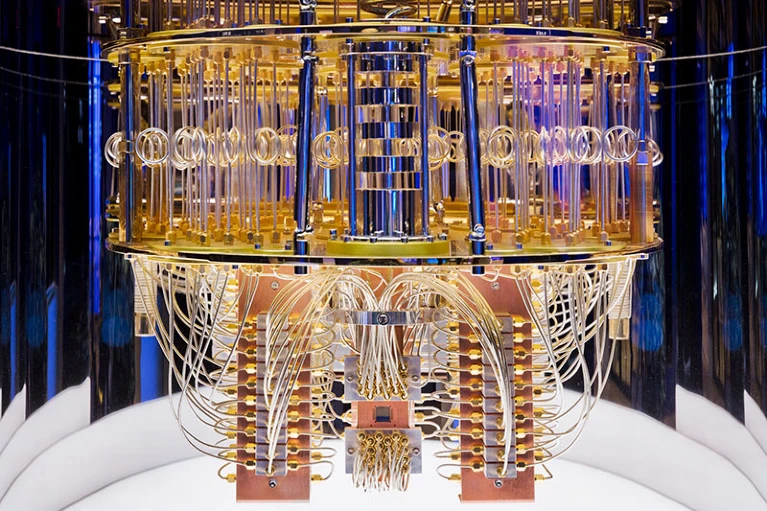

Understanding quantum “magic” operations is essential for design of a quantum computer, such as this one. Credit: IBM.

Starting around the 1980s, the field of quantum computing was born. It was proven that, at least for a few special mathematical problems, a quantum system can perform a computation much more efficiently, in terms of number of required steps, than one limited to non-quantum behavior. This lead to a burst of interest in, and work on, questions about the nature of quantum physics. Theorists could revisit the old questions from the 1930s from a new angle: what attributes of quantum systems were needed to get this extra power? This is a substantial modification, but it has turned out to be a highly productive direction to explore.

Early answers tended to start from the ingredients identified fifty years earlier: superposition and entanglement. For example, some pioneers argued that quantum computers used superposition to do the computation in multiple universes at once 4, while others credited entanglement with allowing for more efficient representations of calculations 5. However, neither of these answers turned out to be fully satisfactory. No other aspect of quantum physics requires one to believe that superpositions actually correspond to multiple instances of reality, so many people were resistant to the many-universes explanation. As for entanglement, an important counter-example was found. For certain specific sets of operations on quantum systems, one can create superpositions and entanglement, but without getting any extra computational power. These operations can be easily and fully tracked by a classical computer with a similar number of operations. Starting from this set, theorists identified a minimum extra operation that allows for the restoration of that extra computational power, and called it a “magic” operation 6. Interestingly, magic operations generate the quantum computational power in a precise and incremental way. One extra magic operation might make your quantum circuit twice as efficient as a classical equivalent, while a second magic operation doubles it again, until it becomes so much faster that completely new capabilities, for all practical purposes, are unlocked. Understanding how these magic operations work has turned out to be an essential part of designing a working quantum computer that is resilient to errors.

Despite the practical importance of magic operations, this still isn’t a great final answer for two reasons. First, we’ve narrowed our focus from all of quantum physics to some specific operations and models. Second, we haven’t given a clear, general picture of what “magic” actually is.

4. Positive Wiger States? Contextuality? (c. 2014)

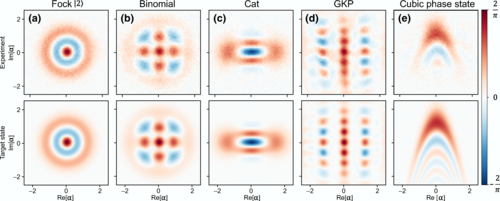

A collection of experimental Wigner distributions for a simple quantum system from a recent paper by the group of Prof. Gasparinetti of Chalmers University. Entirely positive values would simply mean that the measured property has some probabilty of being found in the different values shown, however the presence of negative values (in blue) are only possible in a quantum system.

Fortunately, within the last fifteen years or so, some progress has been made in fleshing out and generalizing the idea of magic and connecting it to other concepts. This is close enough to the present that it is harder to get a clear picture, but I’ll just mention two interesting papers that have contributed to this problem.

First, a generalization of magic, with the technical name of “generalized Wigner negativity”, was shown to be present in any quantum system that has beyond-classical computation 7. This property is a bit difficult to explain intuitively, but roughly it says that such a quantum system cannot be described as a joint probability distribution over its possible states. A Wigner distribution which is always positive is equivalent to a classical probability distrbution, but in a quantum system it can also take negative values.

In a second paper 8, this Wigner negativity was found to be related, not quite universally but in a pretty general case, to the appearence of a property called contextuality. Contextuality means that all observable properties of a system cannot be simultaneously definite. Classical systems never have this feature—whether you measure some property or not, you know that it has some value that you could have gone and looked at. However, for quantum systems this is, strikingly, no longer true.

As an explanation, this is sounding pretty good. It identifies a specific property of quantum physics, which does give it an unintuitive strangeness when compared to our everyday reality, as the ingredient that also gives it extra computational capability. However, this proof still has its limits. It applies to some quantum systems but not all 9. So, it seems to me like it is very suggestive but not the end of the story.

Where are we today?

To be honest, I am not satisfied with any of these answers so far. However, the final work on contextuality seems like a very encouraging partial link between a qualitative, “strange” trait of quantum physics and some of the quantitative consequences. It gives me hope that this question does have a meaningful answer, which we are slowly fumbling our way towards.

I think that the development of this idea is also a nice illustration of a very general phenomenon, which is that progress often comes through new perspectives that let us re-phase old questions in a different way that can be made more concrete and precise. Is information and computation the final such lens for quantum physics, or are there others yet waiting to be found?

I will note in passing that more recent work, like that of W. Zurek, does refine this to give some sense of which superpositions are classically strange and which are not according to the principle of “quantum Darwinism”. ↩︎

This is the “EPR paper”, which is famous enough to have its own Wikipedia page ↩︎

Still treading over well-worn ground at this point, for which Wiki has a reasonable overview ↩︎

This view is most closely associated with D. Deutsch, and is developed in his books such as The Fabric of Reality (1997). ↩︎

This view is developed in the entertaining and readable paper by A. Steane, “A quantum computer only needs one universe” (2000, rev. 2003). ↩︎

A key result here is the Gottesman-Knill theorem, first presented (as far as I know) by Gottesman in this paper (1998). The term “magic” for these operations was introduced, as far as I know, in this paper (2004) by Bravyi and Kitaev. ↩︎

Mari and Eisert, “Positive Wigner Functions Render Classical Simulation of Quantum Computation Efficient” ↩︎

Howard et al, “Contextuality supplies the ‘magic’ for quantum computation” ↩︎

In particular, it only completely works for Hilbert space dimensions of odd prime values. ↩︎